The second report on queuing in BA, with the benefit of seven months more experience.

To read the first one click here.

“An Englishman, even if he is alone, forms an orderly queue of one.” (Mikes 1946)

When George Mikes wrote this in 1946, he was, of course, poking fun at the proper English obsession with queuing, an obsession that Australians have inherited and made their own. This report reflects upon experiences of queuing in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from the perspective of an Australian who has been living in the city for approximately nine months, and makes comparisons with observations and discussions of queuing made approximately six weeks after first arriving in the country. I chose the topic, although it seems trivial, because of confusion I felt when lining up to purchase items, which was compounded by frustration associated with not understanding the language. Little things that I did not expect before my arrival created a greater cultural shock for me than more important issues for which I had an existing preconception.

The original observations of queuing in Buenos Aires focused mainly on the ‘double-line system’ which is employed in a number of different businesses in the city including bars, clubs, pharmacies, bakeries and stationery stores amongst others. The system basically involves waiting in two lines, one in which the cash transaction is made, and the other in which the desired goods are received. The report pointed out the unfamiliarity that an Australian (or other foreign) customer felt with the system, hypothesised possible reasons for its use, outlined some of the connotations it has for a foreigner’s view of the average Argentinean, and concluded that it would be better for all involved if the system were changed. Some of the possible reasons hypothesised for its use included:

• A distrust of customers. By requiring that cash payments occur before exchange of goods, there is less of a chance of theft.

• A distrust of employees. By isolating the cash exchange to a single point, or a few points, if money goes missing it can be tracked to a single employer.

• It is a tradition inherited from colonial ancestors.

• It actually saves time for the customer because people are served more quickly at the cash register. In Australia for example, an employee serving a customer often has to wait for another employee to get access to the cash register.

• It provides a greater profit to the business if a ticket is lost and not redeemed or prints incorrectly and cannot be deciphered.

The connotations that the report claimed were implied by these possible reasons were that Argentineans are dishonest, poor, lacking in education or technical know-how, behind the times, resistant to change and not savvy business people.

A factor in my early views of the double line system and the connotations of its use may have been the fact that I had been robbed twice in my first few months in the country. Having never been robbed ever in Australia, nor in any other country to which I have travelled, to be robbed twice in a few months was a shock. It encouraged my view of the dishonest, poor Argentinean who was willing to take advantage of someone for their own personal gain. The security consciousness of my teachers at university, and the fact that eighty percent of the foreigners I knew had been robbed (some of them twice or three times) reinforced this view. One teacher related a story about how he had found a wallet containing only cash, and a gym membership card. We asked him what he did and he told us he was not willing to tell the employees of the gym that he had one of their members’ wallets because he thought one of them might pretend to be the member. He said he could not take it to the police, because he did not trust them and thought they would take the money. He eventually managed to return the wallet, money and all, which showed me that honest Argentineans existed, but the story that surrounded it reinforced exactly the opposite. In the end, I think I was partly at fault in the robberies for not being more careful, and I could eventually forgive my robbers because of their obvious state of need. Thankfully I have not been robbed since and my view of Argentineans as dishonest has changed.

My views of the double line system however, remain somewhat intact. It is still something I view as inefficient and slightly annoying, but I have become used to it. Although the issue may seem trivial to someone who has not experienced it, it remains a popular topic of conversation amongst new arrivals to the city. Opinions expressed during these conversations are usually negative, focusing on confusion with the purpose for the system and/or derision of the system. This shows that it is, at least, something very noticeable to foreigners. The reason for its noticeability is because, to an Australian (or to most foreigners in general), it is confronting. And it is confronting for two reasons. The first is because it causes a moment of confusion which forces you to realise you are in a foreign place, and which broadcasts to everyone in your immediate vicinity that you are a foreigner. The second is because it is inconvenient. Lining up for something twice is simply not fun. You remember the experience because it is unpleasant, and you try to avoid being embarrassed or inconvenienced in the future.

What makes that embarrassment or inconvenience harder to deal with is the associated difficulty in comprehending the reasons for the system. When something is different to what someone is used to and the reasons for it cannot be easily rationalised, it turns into something unnecessary and unwarranted, or even something stupid. This is evident in everyday life, but is particularly prevalent when someone experiences a new culture. It is a manifestation of culture shock (Hofstede & Hofstede 2005); as you learn about how things function in a new place, if they are not quite the same as what you are used to, they tend to be seen in a negative light. Compare this with an Argentinean’s opinion of the double line system: They rarely have one. It is something they are accustomed to and take for granted. When conversing about it, they often ask what is different about queuing in countries like Australia, and when it is explained, they do not think it is necessarily better or worse than what occurs in Buenos Aires. And perhaps it is not. In the end, what makes something better or worse than something else? Only your experience and your opinion.

With time, the double line system is something that a visitor to Buenos Aires becomes used to. In fact, my first report probably over exaggerated the number of businesses that employ it. There are pharmacies which do not use the system. There are bars which employ bar staff who handle the money directly. There are stationery shops where you can buy a pen without having to describe it in detail first. I found from personal experience that I actually began to avoid places with the double line system. This was particularly true of bars, but also applied to pharmacies. In the case of pharmacies, I would choose to go to the ones with a supermarket style browsing system followed by the cash payment. In the case of bars, I stopped going to the ones where I had to line up twice. As someone starts to settle into life in a new a city and leaves the exploration phase of the visit, they naturally do not see as many places as they were seeing before, and therefore do not see as many places employing the double line. More time is spent at home, at friends’ homes, or at places which are comfortable and familiar.

However, the major factor in becoming used to or tolerating the system is familiarity with it. Upon visiting a bakery with the system, the next time you return, you know what to do and where to go. Progression with the language also helps, so that later, if you enter a shop which employs the system, it can be explained to you. Avoiding the double line system, and settling into life in the city have played their parts in allowing it to become easier to deal with, but in the end familiarity with the system and accepting that you will be lining up twice before you do it is what makes it less annoying. Lining up twice is simply not as much of a big deal to me anymore. There are more important things to worry about.

An increase in familiarity is what marks the change between cultural adjustment and being culturally adjusted, or as Hofstede & Hofstede (2005) call it, acculturation and a steady state. When I first arrived, there were many things that I found unusual about the city. There were ‘big’ things like the language, the way the city looked and homeless children. These were obvious and to an extent, things that I had been expecting. But there were little things which were unusual also. Things like the twenty five and fifty centavo (cent) pieces being the same size, the broken footpaths covered in dog droppings, the difference in the comfort of cinema seats, and letting women on the bus first just because they are women. I definitely experienced the culture shock that Hofstede & Hofstede (2005, p. 323) write about, and if my feelings towards the new environment were not hostile, they were certainly condescending. I felt like Sydney was better than Buenos Aires in so many ways. ‘Why would a country which thought about anything for longer than five minutes make the twenty five and fifty cent pieces the same size?’, I would often think to myself (and rant to others). To me, with our beautiful, differently shaped and sized Australian coins and coloured plastic banknotes, it seemed utterly insane that someone in power could have decided to make different denominations of coins the same size. Exchanging currency is a fundamental part of most peoples’ daily lives, and when coins look, feel and weigh the same, it makes those daily lives just that little bit harder. The double line system, because I could not understand the reasons behind it, fell into the same category.

I suppose it is a reflection on my time here that if I have been preoccupying myself with issues such as the size of coins and whether I have to line up twice, it must mean that life in Buenos Aires has been an enjoyable experience overall. I will definitely be sad to leave, but at the same time I am looking forward to getting back to Sydney, to what I am used to, and where my friends and family are. I feel a little embarrassed about my original analysis of the double line system. I do not think I really had any right to criticise it so harshly, and I certainly did not have the right to imply some of the things about the people that I implied. In the end, the system works. You line up (twice), and you get what you need. Who am I, as a foreigner, to say that it should be replaced, or altered, or stopped? These are things that are decided by the culture, and something that a foreigner has to accept.

And for the record, as any Argentinean will tell you, the twenty five and fifty cent coins are slightly different sizes.

REFERENCES

Hofstede, G.H. & Hofstede, G.J. 2005, Cultures and organizations software of the mind, 2nd edn, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Mikes, G. 1946, How to be an alien : a handbook for beginners and advanced pupils, Wingate, London & New York.

Saturday, November 27, 2010

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Cultural Queues in Buenos Aires, Argentina

This was an assignment I wrote soon after I arrived in Buenos Aires in March sometime. The point of it was to reflect upon an aspect of the culture within the city that had struck me after six weeks living there. Instead of writing about the Tango or the food or something interesting like that, i decided to do my report on queues. The thing about this assignment was that it had to be followed up by another piece of writing, looking at the same subject but with the benefit of roughly seven months more experience. That report will be posted shortly too. This is the exact version i submitted. Thank you to those on face-book i wrote to rally up ideas.

“An Englishman, even if he is alone, forms an orderly queue of one.” (Mikes 1946)

When George Mikes wrote this in 1946, he was, of course, poking fun at the proper English obsession with queuing, an obsession that Australians have inherited and made their own. There’s nothing worse than a queue-jumper. It’s not fair. It’s not right. It’s un-Australian. This report explores the cultural aspects of queuing in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from the perspective of an Australian customer and discusses the ways in which their queuing systems reflect upon Argentina’s appearance to outsiders.

Australians are world famous for their queuing. From an early age, young Australian queue jumpers are sent to the back of the line. If there are multiple Automatic Teller Machines available at a bank, Australians will form a single orderly queue, minimizing average waiting time and maximizing efficiency. Australians will always make sure those already at the bar have been served. Australians have a definite sense of social justice when it comes to queuing and it effects how they view the rest of the world.

Now, no matter who or where you are in the world, queuing to receive a service is usually not a pleasant experience. People don’t like to wait for a number of reasons. Amongst many others, they feel like they are wasting time, could be doing something more productive, or don’t like close contact with strangers. There are entire scientific journals, such as Queueing Systems which are devoted to the mathematics and mechanics of queues, and continue to research ways of making queues more efficient and productive for use in areas such as health, traffic, business and the internet. There are also many scholarly articles which discuss the social aspects of queuing and the notions of fairness, fear and anger that can be experienced while queuing.

From an Australian perspective, Porteños, or people from Buenos Aires, certainly aren’t the worst queuers in the world. When the line is short with a single server, like a line for train tickets, they will rarely jump ahead. If there is a person ahead of them near a service point, they will often ask if they are waiting in line. This is entirely different from many places in Asia or Europe, where the concept of queuing equals pushing to the front or loitering near a service point in order to dart in when it becomes available.

However, in Buenos Aires, as in many South American countries, there is a particularly unusual method of queuing (as it appears to an Australian). It can be experienced at large bars, fast food chains, bakeries, photo shops, retail outlets, pharmacies, stationary stores and many other places. This method generally involves waiting in two lines. In one of the lines, the cash transaction is made, while in the other, the desired goods are received.

The order in which a customer waits in these two lines is dependent on the business, but generally, at places such as large bars, or fast food outlets, the cash line is stood in first, a ticket received, and this is then given to the server who reads the ticket and presents the food, drinks, or whatever else is desired.

In other places, such as bakeries, pharmacies, and stationery stores, goods are chosen with the help of an attendant, after waiting in line to access that attendant, and usually presented by the attendant to the cashier for payment. It’s almost like a supermarket, but with someone picking the items you choose off the shelf, and putting them in a trolley you don’t have access to.

The two-line method can be a frustrating, annoying, stressful, and confusing experience for an Australian customer, because it essentially doubles the waiting time they’re used to. It can even mean tripling the waiting time if the customer is unfamiliar with the process; one line to get the product, only to be told a ticket is needed, a second line to get the ticket, and finally the return to the end of first line to get the product.

The two-queue system appears so inefficient to a foreign customer that it’s hard to imagine that there must be a legitimate and beneficial reason for it. A foreigner’s experiences of daily life within a country affect their views of the people from that country and something as simple as a queuing system is no exception. Quick opinions are often formed through conjecture due to an inability or disinterest to gain facts. The following attempts to replicate some of the quick opinions that may be formed and is based solely upon conjecture.

An obvious possible reason for the two line system might be to more easily monitor those persons in contact with the cash. In the two-line system, responsibility for the cash in the register often lies with just a single person. This reduces the temptation a cashier might have to steal money because they can be more easily monitored. If one takes this as the reason for the two queues, the Australian’s impression of Argentineans becomes one of dishonesty and distrust. Argentineans themselves have a phrase for their dishonest nature; la viveza criolla, meaning the cunning native. Employees appear willing to steal from their employers given the chance, and employers appear distrustful of the people they employ.

Once an outsider jumps to this conclusion, it’s easy to jump to others. A popular conclusion amongst foreigners is that many Argentineans working in these positions are so poor they need to steal extra cash to survive. This conclusion is an uncomfortable one, firstly because it assumes that most poor people are thieves, and secondly, because it assumes employers aren’t paying their employees enough to survive.

But perhaps the two line system has more to do with controlling the customer, and stopping them from walking away with goods they haven’t paid for. This is done by making them pay at the cashier first, or by keeping the goods behind the counter until payment. But thefts like this could also be avoided by using a single line if the cash was taken first and products given after payment. Waiting time would be reduced with no risk of ‘walk-aways’. ‘Walk-aways’ are discouraged in countries such as Australia through the use of electronic security devices that detect objects leaving the store that haven’t been paid for.

Three impressions of Argentineans are formed from this; one is that Argentinean customers are willing to steal given the opportunity, reinforcing our notion of la viveza criolla and the dishonest Argentinean. The second has to do with a cultural difference in the importance placed upon customer satisfaction. In Australia if a customer had to continually line up twice, they would complain and possibly not return to the store. The store would lose a customer, and future revenue due to a frustrating wait that could easily be avoided. The third is that Argentineans either don’t have the means or the desire to install electronic security systems, which indirectly reflects on their lack of wealth.

Perhaps the extra security measures are a result of the crash of the Argentinean economy in 2001. After a long period of recession, the peso hit rock bottom, unemployment rose as high as 20%, and the country defaulted on an $80 billion sovereign loan, the largest default in history. Thousands lost their life savings in an instant when bank accounts were frozen, and half the country descended below the poverty line. Under these conditions, it is understandable that an employer would keep a close eye on where his money is going and take measures to ensure it isn’t going into an employee’s pocket. Now, things are recovering. Argentina’s current unemployment rate is around 8% and dropping. But there is an interesting clue to suggest that the crash doesn’t actually have much to do with the use of the two-line system.

That clue is that the double line system is not exclusive to Argentina. Fellow travelers speak of the same system in Chile, Bolivia and Peru. Perhaps, like Australia, these countries have simply inherited their queuing systems from their colonizers. Perhaps the two-line system is traditional.

This seems unlikely though, because, like Australia, Spain currently employs the one-line system. If Spain ever employed the two-line system in the past, they’ve realized its downfalls, and moved on to the more efficient single-line system. I doubt that it’s tradition in Argentina, but if it is, they need to move on, as it’s time consuming.

However, it could be argued that the ticket-first system actually saves time, because access to cash registers is concentrated and servers do not have to wait to use them. There are examples of two line systems in Australia in which this is definitely the case. Examples include pre-paying for bus tickets or train tickets, theatre tickets, movie tickets or concert tickets. However, in all of these cases, the amount of time spent waiting to buy the ticket is usually made up by the amount of time saved when using it.

In Buenos Aires, the likelihood of the two-line system saving time is only good if cash registers are so few that servers must wait for each other to get access to them, or if a person plans to return to the product supply point multiple times with their originally purchased tickets. The simple fact is that the shorter the line, the more products sold because people are less willing to wait longer periods of time. But to create shorter lines, you need to employ more people, and install more cash registers. These things are expensive. So an outsider perceives the lack of cash registers and workers as a lack of money, and Argentineans are again perceived as poor.

Another downfall of the ticketing system, especially in crowded bars, is that if you lose the ticket, you lose the drinks. Obviously if a customer loses a ticket it’s their own fault, but often, when this happens, a customer can’t help but think that the bar knows that some of the tickets are going to get lost, meaning they won’t have to supply the products that been have legitimately been bought. If a person leaves the bar early with tickets in their pocket, again, the bar wins. Also if a ticket doesn’t print correctly and the bar person can’t read it, the drinks disappear. An outsider can’t help but think that the bar does this on purpose, reinforcing our idea of the dishonest Argentinean. If the bar doesn’t do this on purpose, an outsider wonders why they don’t change the system to ensure it doesn’t happen in the future, reinforcing our idea of a cultural difference in the value placed on customer satisfaction.

Another problem at bars is due to the length of the queues. Buenos Aires appears to have a serious problem with overcrowding in night clubs. In late 2004, 194 people were killed and another 714 injured after a fire broke out at the República Cromañón nightclub. Many died of smoke inhalation and many others were crushed to death as people tried to escape through inadequate exits. Because lines are so long to get drinks, people tend to order larger amounts to avoid returning to the queue later. Friends will also get them to cash their tickets to avoid standing in the line themselves.

This can cause confusion between the customer and the bartender. The bartender will take the ticket, serve only some of the drinks, and then move on to another customer. In the meantime, the original customer waits, and tries to say they’re missing a drink, while the rest of the line pushes from behind. The pressure from the line behind eventually causes the customer to leave short-changed. Again, perhaps it’s not purposeful, but an outsider sees it as rude, annoying, and dishonest.

Using queue theory, mathematicians can find the perfect balance between the amount of customers moving through the system and their waiting time, the number of service points and their installation costs, the probability and amount of theft by employees and customers, and customer satisfaction and their likelihood of returning. It’s impossible to know whether that balance has been found in Argentina, and it’s affected by things such as an employee’s level of pay and the value they place on employment. But it certainly appears inefficient, and unless every single employee is a thief, it’s highly unlikely the balance has been found within the current system.

It’s interesting that something as simple as queuing can provide insights into a people and their culture. To an Australian, the two-queue system makes Argentineans appear dishonest, distrustful, inefficient, overly bureaucratic, and unwilling or unable to think of better solutions to problems. Appearances that from experience, are entirely unwarranted. If Argentineans rethink this system, it will not only create better impressions on foreigners, but benefit their economy.

References

Mikes, G. 1946, How to be an alien : a handbook for beginners and advanced pupils, Wingate, London & New York.

“An Englishman, even if he is alone, forms an orderly queue of one.” (Mikes 1946)

When George Mikes wrote this in 1946, he was, of course, poking fun at the proper English obsession with queuing, an obsession that Australians have inherited and made their own. There’s nothing worse than a queue-jumper. It’s not fair. It’s not right. It’s un-Australian. This report explores the cultural aspects of queuing in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from the perspective of an Australian customer and discusses the ways in which their queuing systems reflect upon Argentina’s appearance to outsiders.

Australians are world famous for their queuing. From an early age, young Australian queue jumpers are sent to the back of the line. If there are multiple Automatic Teller Machines available at a bank, Australians will form a single orderly queue, minimizing average waiting time and maximizing efficiency. Australians will always make sure those already at the bar have been served. Australians have a definite sense of social justice when it comes to queuing and it effects how they view the rest of the world.

Now, no matter who or where you are in the world, queuing to receive a service is usually not a pleasant experience. People don’t like to wait for a number of reasons. Amongst many others, they feel like they are wasting time, could be doing something more productive, or don’t like close contact with strangers. There are entire scientific journals, such as Queueing Systems which are devoted to the mathematics and mechanics of queues, and continue to research ways of making queues more efficient and productive for use in areas such as health, traffic, business and the internet. There are also many scholarly articles which discuss the social aspects of queuing and the notions of fairness, fear and anger that can be experienced while queuing.

From an Australian perspective, Porteños, or people from Buenos Aires, certainly aren’t the worst queuers in the world. When the line is short with a single server, like a line for train tickets, they will rarely jump ahead. If there is a person ahead of them near a service point, they will often ask if they are waiting in line. This is entirely different from many places in Asia or Europe, where the concept of queuing equals pushing to the front or loitering near a service point in order to dart in when it becomes available.

However, in Buenos Aires, as in many South American countries, there is a particularly unusual method of queuing (as it appears to an Australian). It can be experienced at large bars, fast food chains, bakeries, photo shops, retail outlets, pharmacies, stationary stores and many other places. This method generally involves waiting in two lines. In one of the lines, the cash transaction is made, while in the other, the desired goods are received.

The order in which a customer waits in these two lines is dependent on the business, but generally, at places such as large bars, or fast food outlets, the cash line is stood in first, a ticket received, and this is then given to the server who reads the ticket and presents the food, drinks, or whatever else is desired.

In other places, such as bakeries, pharmacies, and stationery stores, goods are chosen with the help of an attendant, after waiting in line to access that attendant, and usually presented by the attendant to the cashier for payment. It’s almost like a supermarket, but with someone picking the items you choose off the shelf, and putting them in a trolley you don’t have access to.

The two-line method can be a frustrating, annoying, stressful, and confusing experience for an Australian customer, because it essentially doubles the waiting time they’re used to. It can even mean tripling the waiting time if the customer is unfamiliar with the process; one line to get the product, only to be told a ticket is needed, a second line to get the ticket, and finally the return to the end of first line to get the product.

The two-queue system appears so inefficient to a foreign customer that it’s hard to imagine that there must be a legitimate and beneficial reason for it. A foreigner’s experiences of daily life within a country affect their views of the people from that country and something as simple as a queuing system is no exception. Quick opinions are often formed through conjecture due to an inability or disinterest to gain facts. The following attempts to replicate some of the quick opinions that may be formed and is based solely upon conjecture.

An obvious possible reason for the two line system might be to more easily monitor those persons in contact with the cash. In the two-line system, responsibility for the cash in the register often lies with just a single person. This reduces the temptation a cashier might have to steal money because they can be more easily monitored. If one takes this as the reason for the two queues, the Australian’s impression of Argentineans becomes one of dishonesty and distrust. Argentineans themselves have a phrase for their dishonest nature; la viveza criolla, meaning the cunning native. Employees appear willing to steal from their employers given the chance, and employers appear distrustful of the people they employ.

Once an outsider jumps to this conclusion, it’s easy to jump to others. A popular conclusion amongst foreigners is that many Argentineans working in these positions are so poor they need to steal extra cash to survive. This conclusion is an uncomfortable one, firstly because it assumes that most poor people are thieves, and secondly, because it assumes employers aren’t paying their employees enough to survive.

But perhaps the two line system has more to do with controlling the customer, and stopping them from walking away with goods they haven’t paid for. This is done by making them pay at the cashier first, or by keeping the goods behind the counter until payment. But thefts like this could also be avoided by using a single line if the cash was taken first and products given after payment. Waiting time would be reduced with no risk of ‘walk-aways’. ‘Walk-aways’ are discouraged in countries such as Australia through the use of electronic security devices that detect objects leaving the store that haven’t been paid for.

Three impressions of Argentineans are formed from this; one is that Argentinean customers are willing to steal given the opportunity, reinforcing our notion of la viveza criolla and the dishonest Argentinean. The second has to do with a cultural difference in the importance placed upon customer satisfaction. In Australia if a customer had to continually line up twice, they would complain and possibly not return to the store. The store would lose a customer, and future revenue due to a frustrating wait that could easily be avoided. The third is that Argentineans either don’t have the means or the desire to install electronic security systems, which indirectly reflects on their lack of wealth.

Perhaps the extra security measures are a result of the crash of the Argentinean economy in 2001. After a long period of recession, the peso hit rock bottom, unemployment rose as high as 20%, and the country defaulted on an $80 billion sovereign loan, the largest default in history. Thousands lost their life savings in an instant when bank accounts were frozen, and half the country descended below the poverty line. Under these conditions, it is understandable that an employer would keep a close eye on where his money is going and take measures to ensure it isn’t going into an employee’s pocket. Now, things are recovering. Argentina’s current unemployment rate is around 8% and dropping. But there is an interesting clue to suggest that the crash doesn’t actually have much to do with the use of the two-line system.

That clue is that the double line system is not exclusive to Argentina. Fellow travelers speak of the same system in Chile, Bolivia and Peru. Perhaps, like Australia, these countries have simply inherited their queuing systems from their colonizers. Perhaps the two-line system is traditional.

This seems unlikely though, because, like Australia, Spain currently employs the one-line system. If Spain ever employed the two-line system in the past, they’ve realized its downfalls, and moved on to the more efficient single-line system. I doubt that it’s tradition in Argentina, but if it is, they need to move on, as it’s time consuming.

However, it could be argued that the ticket-first system actually saves time, because access to cash registers is concentrated and servers do not have to wait to use them. There are examples of two line systems in Australia in which this is definitely the case. Examples include pre-paying for bus tickets or train tickets, theatre tickets, movie tickets or concert tickets. However, in all of these cases, the amount of time spent waiting to buy the ticket is usually made up by the amount of time saved when using it.

In Buenos Aires, the likelihood of the two-line system saving time is only good if cash registers are so few that servers must wait for each other to get access to them, or if a person plans to return to the product supply point multiple times with their originally purchased tickets. The simple fact is that the shorter the line, the more products sold because people are less willing to wait longer periods of time. But to create shorter lines, you need to employ more people, and install more cash registers. These things are expensive. So an outsider perceives the lack of cash registers and workers as a lack of money, and Argentineans are again perceived as poor.

Another downfall of the ticketing system, especially in crowded bars, is that if you lose the ticket, you lose the drinks. Obviously if a customer loses a ticket it’s their own fault, but often, when this happens, a customer can’t help but think that the bar knows that some of the tickets are going to get lost, meaning they won’t have to supply the products that been have legitimately been bought. If a person leaves the bar early with tickets in their pocket, again, the bar wins. Also if a ticket doesn’t print correctly and the bar person can’t read it, the drinks disappear. An outsider can’t help but think that the bar does this on purpose, reinforcing our idea of the dishonest Argentinean. If the bar doesn’t do this on purpose, an outsider wonders why they don’t change the system to ensure it doesn’t happen in the future, reinforcing our idea of a cultural difference in the value placed on customer satisfaction.

Another problem at bars is due to the length of the queues. Buenos Aires appears to have a serious problem with overcrowding in night clubs. In late 2004, 194 people were killed and another 714 injured after a fire broke out at the República Cromañón nightclub. Many died of smoke inhalation and many others were crushed to death as people tried to escape through inadequate exits. Because lines are so long to get drinks, people tend to order larger amounts to avoid returning to the queue later. Friends will also get them to cash their tickets to avoid standing in the line themselves.

This can cause confusion between the customer and the bartender. The bartender will take the ticket, serve only some of the drinks, and then move on to another customer. In the meantime, the original customer waits, and tries to say they’re missing a drink, while the rest of the line pushes from behind. The pressure from the line behind eventually causes the customer to leave short-changed. Again, perhaps it’s not purposeful, but an outsider sees it as rude, annoying, and dishonest.

Using queue theory, mathematicians can find the perfect balance between the amount of customers moving through the system and their waiting time, the number of service points and their installation costs, the probability and amount of theft by employees and customers, and customer satisfaction and their likelihood of returning. It’s impossible to know whether that balance has been found in Argentina, and it’s affected by things such as an employee’s level of pay and the value they place on employment. But it certainly appears inefficient, and unless every single employee is a thief, it’s highly unlikely the balance has been found within the current system.

It’s interesting that something as simple as queuing can provide insights into a people and their culture. To an Australian, the two-queue system makes Argentineans appear dishonest, distrustful, inefficient, overly bureaucratic, and unwilling or unable to think of better solutions to problems. Appearances that from experience, are entirely unwarranted. If Argentineans rethink this system, it will not only create better impressions on foreigners, but benefit their economy.

References

Mikes, G. 1946, How to be an alien : a handbook for beginners and advanced pupils, Wingate, London & New York.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

One more song...

To add to the list of 10 below is this one;

We no speak Americano by Yolanda Be Cool and DCUP.

You really can't get away from this song here. It's played everywhere. It's hugely popular and has been for at least the last three months. And I've just realised that it's Australian. Go Aussies! It's just a pity that something a little less annoying couldn't be a popular Aussie song.

We no speak Americano by Yolanda Be Cool and DCUP.

You really can't get away from this song here. It's played everywhere. It's hugely popular and has been for at least the last three months. And I've just realised that it's Australian. Go Aussies! It's just a pity that something a little less annoying couldn't be a popular Aussie song.

Sunday, November 7, 2010

I haven't blogged in ages.

And i don't really know why. Lots has happened which i coulda wrote about. For example, i still haven't written about how i moved into a new place with an Argentinean woman (who's our age - we're adults) who has a cat that's called Malbec, which is a type of grape that's used in wine here and is pretty tasty, and the cat is really strange, because it meows a lot and it always attacks people. And i moved into this place before i went on the trip with the Bren Dog which was quite long ago now.

Another thing i've been doing is I've been taking spanish classes at a private school, which i also haven't written about, and i've been taking them because the classes at La UCA are a hopeless joke. They're a joke, but a really unfunny one. Like a joke about chickens crossing the road or something. Or this one in Spanish:

- Mi hijo, en su nuevo trabajo, se encuentra como pez en el agua.

- Qué hace?

- Nada

Don't worry if you don't speak Spanish. Let me just tell you that it's not a very funny joke.

And Em got called the best teacher in the world by one student.

And in one spanish class, my teacher asked us to discuss abortion.

And last night i went to a gay bar with a new friend who has the same last name as me.

I mean... c'mon. I should be blogging that, right?

But look...

I've finished another assignment this week, and i've only got one to go, and Argentinean uni finishes in a couple of weeks, and dad arrives in a few days, and there's the possibility of my little brother coming to visit, so...

...i'm gonna write more things on this blog...

I can just imagine you're all giddy with anticipation.

Another thing i've been doing is I've been taking spanish classes at a private school, which i also haven't written about, and i've been taking them because the classes at La UCA are a hopeless joke. They're a joke, but a really unfunny one. Like a joke about chickens crossing the road or something. Or this one in Spanish:

- Mi hijo, en su nuevo trabajo, se encuentra como pez en el agua.

- Qué hace?

- Nada

Don't worry if you don't speak Spanish. Let me just tell you that it's not a very funny joke.

And Em got called the best teacher in the world by one student.

And in one spanish class, my teacher asked us to discuss abortion.

And last night i went to a gay bar with a new friend who has the same last name as me.

I mean... c'mon. I should be blogging that, right?

But look...

I've finished another assignment this week, and i've only got one to go, and Argentinean uni finishes in a couple of weeks, and dad arrives in a few days, and there's the possibility of my little brother coming to visit, so...

...i'm gonna write more things on this blog...

I can just imagine you're all giddy with anticipation.

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Rainy Day in BA

Monday, August 23, 2010

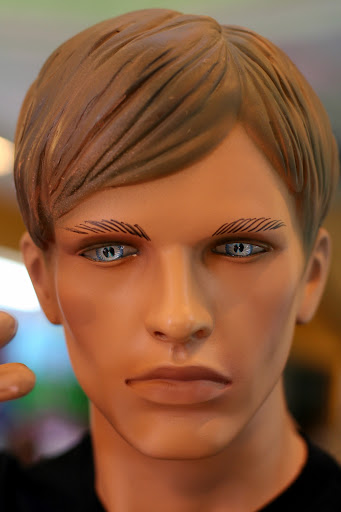

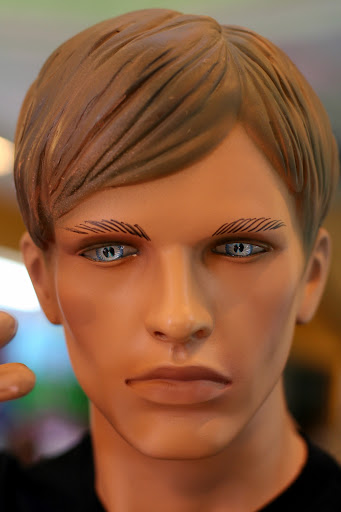

Mannequins of La Paz

We saw these mannequins in and around the Mercado Negro in La Paz. Brennen and I thought they were hilarious. Em, less so.

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

Ten songs I've heard a lot of in Argentina

Here's a list of ten songs (in no particular order) which I've heard ad nauseam since my arrival in Argentina. If you're only going to listen to one, make it number 10.

1. Sexy Bitch – David Guetta featuring Akon

If this list was to be in order, this would be at the top of it. I've heard this song so many times its not funny anymore. But it's still offensive.

2. Poker Face – Lady Gaga

Incredibly over-played. Sometimes three times an hour, depending on the station. My least favorite song on the list. It's simply annoying.

3. Guapa - Diego Torres

Quite a catchy song. He's the only currently active Argentinean on the list. I've heard this song a lot partly because he does an advertisement for head and shoulders and they use the song in it.

4 .Waka Waka - Shakira

Don't know if it was the same everywhere else, but you couldn't get away from this song during the world cup. You may not have heard the Spanish version.

5. Waving flag – K’naan w/ David Bisbal.

This one too. Every game... Be careful if you are offended by product placement.

6. Si No Te Hubieras Ido - Marco Antonio Solís

This guy's Mexican. And off-the-charts cheesy.

7. Te vas – Grupo 5

Peruvian group with a massive body of work. Catchy song. A fine example of Cumbia.

8. Egoista – Belinda ft Pitbull

Belinda's originally Spanish, now living in Mexico. Pitbull grew up in Miami Florida, and calls himself Cuban-American.

9. Por Una Cabeza – Carlos Gardel

Carlos Gardel is one of Argentina's national heroes. He wrote and originally sang this song, but this version is the one you see in 'Scent of a Woman', with the violin played by Itzhak Perlman. I'm not an expert, but this is probably a pretty bad example of tango dancing.

10. Adios Nonino - Astor Piazzolla

The original of this one also had lyrics, but this is Bob Zimmerman’s (Not that Bob Zimmerman...) interpretation, arranged for the royal dutch wedding of Prince Willem Alexander to Princess Máxima (Máxima Zorreguieta). Astor Piazzolla was also Argentinean.

1. Sexy Bitch – David Guetta featuring Akon

If this list was to be in order, this would be at the top of it. I've heard this song so many times its not funny anymore. But it's still offensive.

2. Poker Face – Lady Gaga

Incredibly over-played. Sometimes three times an hour, depending on the station. My least favorite song on the list. It's simply annoying.

3. Guapa - Diego Torres

Quite a catchy song. He's the only currently active Argentinean on the list. I've heard this song a lot partly because he does an advertisement for head and shoulders and they use the song in it.

4 .Waka Waka - Shakira

Don't know if it was the same everywhere else, but you couldn't get away from this song during the world cup. You may not have heard the Spanish version.

5. Waving flag – K’naan w/ David Bisbal.

This one too. Every game... Be careful if you are offended by product placement.

6. Si No Te Hubieras Ido - Marco Antonio Solís

This guy's Mexican. And off-the-charts cheesy.

7. Te vas – Grupo 5

Peruvian group with a massive body of work. Catchy song. A fine example of Cumbia.

8. Egoista – Belinda ft Pitbull

Belinda's originally Spanish, now living in Mexico. Pitbull grew up in Miami Florida, and calls himself Cuban-American.

9. Por Una Cabeza – Carlos Gardel

Carlos Gardel is one of Argentina's national heroes. He wrote and originally sang this song, but this version is the one you see in 'Scent of a Woman', with the violin played by Itzhak Perlman. I'm not an expert, but this is probably a pretty bad example of tango dancing.

10. Adios Nonino - Astor Piazzolla

The original of this one also had lyrics, but this is Bob Zimmerman’s (Not that Bob Zimmerman...) interpretation, arranged for the royal dutch wedding of Prince Willem Alexander to Princess Máxima (Máxima Zorreguieta). Astor Piazzolla was also Argentinean.

Monday, August 9, 2010

Bolivia

The bus was an overnighter, and I woke early in the morning, unable to get back to sleep. We eventually arrived at the border crossing between Peru and Bolivia, a town on Lake Titicaca called Desaguadero. The crossing was a slight nightmare, with an initial line-up on the Peruvian side of about an hour and a half. The streets were absolutely packed with people, and cars and buses had a very hard time getting through.

Once we had passed Peruvian formalities, we crossed a bridge and waited in the line for the Bolivian side of things. Brennen discovered that he had to pay a visa fee of US$135, which needless to say, he was not happy about. After clearing Bolivian customs, we waited for the bus to make its way through the throngs of people and eventually rejoined it. But it was missing some passengers, so we had to wait another hour or so until everyone was on board.

It was three more hours to La Paz and we arrived at about 1.30pm, two and a half hours behind schedule. From the bus station, we walked down the hill to Plaza San Francisco and found a hostel, which was more like a hotel. It had hot showers, and private bathrooms. Luxury. Brennen hadn’t had a hot shower since he left Salta, about two weeks earlier. My last proper hot shower was in San Pedro de Atacama.

But before showering, I went to email Emily with our location. There was an email from her waiting for me that said she was very sick. Unu was correct again - she was going to need a hug. Brennen and I relaxed in luxury in the hotel for the afternoon, and I went to collect Emmo from the airport at 8pm. When she came out of the gates, she looked utterly terrible – totally grey. She’d been vomiting all the night before, and was still feeling terrible. And now she had flown directly to La Paz from sea level, adding altitude sickness to the mix.

We jumped in a cab and headed straight to the hotel where she remained for the night, while Brennen and I went out to get some street meat for dinner and then a beer at a Cuban bar.

The next morning after sleeping in a little bit, Emmo was feeling better, so we headed out to the Mercado Negro (Black Market). We walked around a bit, and saw some hilarious mannequins around the place. Brennen and I were giggling like school girls at them. Em found them less amusing. I’ll put pictures up of them up in another post.

We kept walking around and then a man tried to pickpocket me. I caught him in the act, and called him a thief, looking around to see if anyone cared. No one did. I grabbed his arm and said it again, to which he responded ‘Que pasa!!’, and pushed me away. It wasn’t really worth pursuing, because I’d caught him before he got anything, so he just walked away. But I spent the rest of the morning with my hands in my pockets and my camera stowed safely away, feeling very uncomfortable.

After the market, we headed to a lookout in a park called Laikakota, on top of a small hill near the centre of town. It was full of play equipment and families having fun, and the view was quite nice too.

Em and the Bren-dog at Laikakota.

Panoramic view of La Paz from the lookout

We headed back to the hotel to rest for a while and Brennen randomly bumped into Yasmin when he was getting money from the ATM. She was meeting up with Alex and Luci at a nearby restaurant, two girls from Uni who are doing their exchange in Santiago, Chile. We were invited to come along, and joined them at an Indian/Thai/Japanese/Korean (let’s just call it Asian) restaurant which had utterly, utterly terrible service, but quite good food. It would have been nice to know what the dish I ordered had tasted like, but the one they brought me was fine...

The next morning we headed to the Cementario district to find a bus to Copacabana on Lake Titicaca. The bus was relatively easy to find, despite a taxi driver who was going to Desaguadero being particularly unhelpful;

- 'Where's the bus to Copacabana?'

- 'I'm going to Desaguadero, wanna come?'

- 'No, we want the bus to Copacabana.'

- 'What about Desaguadero?'

We boarded the bus for 15 Bolivianos and in around three hours we were in Copa – Copacabana. The price didn’t include a ferry crossing where we had to get off and take a smaller boat for 1.5 Bolivianos while the bus went across (looking slightly unsafe).

Once in Copacabana, we were accosted by people trying to sell us their hostels, and decided to head towards Hostal Sonia, on the corner of Tejada and Murillo. It was a nice place, with a roof-top terrace and a big room with private bathroom and a view of the lake. We checked in and headed down to the beach to have a trouty snack, and a beer while we played cards and watched the sun approach the horizon.

View from the roof of Hostal Sonia

Brennen and I decided to head up the hill to the north of the town, Cerro Calvario, but Em was still feeling the altitude, and decided to remain behind. We walked most of the way up quickly, watched the sunset and headed down when it was getting dark.

Sunset over Lake Titicaca from Cerro Calvario

Copacabana from Cerro Calvario at sunset

Moonrise over Copacabana

We headed home to play cards and book a ticket to the Isla del Sol for the following morning at 8.20.

The boat didn’t really leave Copacabana until about 9.20 and we arrived at the northern port of Isla del Sol (Cha’llapampa) at about 11.30. We were met by a man called Jorge who told us he’d be taking us on a tour of the island. But he wasn’t very good, and managed to lose half of us in the first five minutes. We saw a small museum near the port, and then continued on to the ruins of the temple of the virgins of the sun, and then to Chincana. Then, once the tour was over, he told us that he doesn't earn a salary, and the cost of the tour would be 20 Bolivianos per person. We gave him 10 each. My god we’re cheap. That’s about 1.5 US dollars.

The packed boat on the way to the Isla del Sol

We were planning to walk the 15 or so kilometres back to the Fuente del Inca, where we could catch a return ferry, but with the ferry arriving late to the Isla del Sol, and the tour taking much longer than we expected, it was going to be a crazy rush. The walk was very difficult due to the sun and the altitude, and we really had to push it to make it back to the ferry in time. We almost felt like the tour had been slow on purpose to make us miss the boat and buy another return ticket.

View of Lake Titicaca from the path to Fuente del Inca.

We made it back to the port as the ferry was pulling away, but it was very full, and the driver asked us if we wanted to get the later one. There was a later one? We didn’t know that, and had ended up pushing ourselves to make it to the jetty for no reason. The later one was scheduled to leave at 4pm (in half an hour), but didn’t end up actually going for another hour. We were back in Copacabana by about 5.45, got some dinner and had an early night.

On the ferry back to Copacabana

The next morning we got up early and headed into town to get a bus back to La Paz. It was easy to find a lift, and we were out of Copacabana by about 9am. The ride back to La Paz was uneventful, and once we were back, we headed to the bus station to buy tickets to our relative destinations. Brennen found a 40 hour bus leaving for Buenos Aires immediately (or so he thought) and Em and I booked a bus to Uyuni leaving that night at 8pm. When I was back in BA I found out that Brennen’s trip had actually taken 4 days. If he can be bothered writing about it, I’ll post his nightmare here.

Em and I left our bags with the bus company and had a little wander around La Paz before deciding to go and see a movie. We saw the Karate Kid, which was almost a word for word remake of the original. And quite enjoyable. My favourite scene – Jackie Chan beating up a bunch of 12 year olds.

Then it was back to the bus station and on to Uyuni, after being warned by a traditionally dressed man that we’d need a blanket for the trip. For some reason, we ignored him and threw our bags into the luggage compartment of the bus...

The bus left on time, and we initially got some sleep, but woke at about 1am, frozen to the bone, when the bus made a stop. I jumped off and luckily, some other people were rearranging their things in the baggage-compartment. I saw my bag, grabbed it, and removed the sleeping bag.

From then on things were slightly more comfortable. Em and I huddled under the blanket and got a little more sleep before waking when the sun was rising. The windows of the bus were frozen, as was my water bottle. It’s a little hard to see in the photo, but trust me - it was frozen.

Our bus window as the sun was coming up.

My frozen water bottle

Arriving in Uyuni, we were immediately accosted by people trying to sell us their tour of the region. We were pleased to hear that there were tours leaving that morning at around 11, meaning that we wouldn't have to stay in the town of Uyuni for the night. Everyone seemed to offer the same price – 600 B for three days - so we went with one of them to their office and got organized - had some breakfast, bought some warm things like scarves and gloves, and left for the tour with a French couple who didn't speak much English, and a Belgian couple who did.

OK, the commentary for this section is going to be more boring than normal. We went to a lot of places, OK? So just look at the photos if you get sick of it.

The first stop was the train cemetery about three kms from the centre of town. It was at this stage we realized just how many other people there were doing the same tour. There were about 20 other jeeps and people climbing all over the train engines.

These train tracks were actually still in use.

Next stop was Colchani with its ‘museums’, which could be more accurately described as ‘shops which sell tourist crap’. I took this photo of a car that could've used a lick of paint.

Next stop was the Salar (salt flat) itself, and some of the areas that are being mined for salt. It’s the biggest salt flat in the world with an area of 12,000 km2. Then we visited a hotel made of the stuff.

The salar with little mountains of salt ready to be collected and refined

Next was Isla Incahuasi, aka Isla de los Pescadores with its huge cacti (some of which are over 1000 years old) and it’s geographically isolated community of Viscachas. We climbed to its lookout and had lunch there, and then Em and I walked around the island.

That’s me next to a huge cactus on Isla Incahuasi

I suppose you’ve gotta do one of these when you’re there. It’s worked surprisingly well considering it was a self-timer shot.

Next stop was a place that they collect salt blocks to make buildings, or to carve into touristy trinkets such as salt llamas or ashtrays.

The salt block collection place

An interesting salt crystal which I picked up out of an evaporation pool

Salt encrusted hands.

Then we headed to our lodgings for the night – a hotel made entirely of salt. I wouldn’t have liked to work there because there was a constant mist of salt dust in the air and I felt thirsty the entire time we were there. Not to mention it was frickin’ freezing.

The salt hotel

Sunset from the salt hotel

My God, dinner was ordinary that night. I think they call it Pique a lo Macho, a tradition Bolivian dish. It consists of French fries with chopped hotdog meat, boiled eggs, fried onions and tomatoes heaped into a brown mushy pile. No one could finish a whole plate.

We were up early the next morning, woken by the guide. It was absolutely freezing before sunrise. The guide told us it got to minus 20 outside during the night. We left the hotel around 7.20 and visited the town of San Juan at about 8.15.

Then we passed thru Salar de Chiguana, the military post at Chiguana, and stopped to get a photo of the Ollague Volcano.

Volcan Ollague.

Then – Lagunas Canapa and Hedionda (where we lunched) and some beautiful Jame’s Flamingoes.

Flamingoes at Laguna Canapa

Flamingos in flight at Laguna Hedionda

Flamingos in flight again at Laguna Hedionda

Then we passed Laguna Chiar Kota, Laguna Honda and Laguna Ramaditas, then through an unusual rocky valley filled with more viscachas, and then continued to La Montana de Siete Colores, el Desierto Siloli and stopped at the Arbol de Piedra.

Em with the Arbol de Piedra (Tree Rock)

Then on to Laguna Colorada, which is coloured red due to the algae that live in its waters.

Laguna Colorada

We stayed the night in a hotel called San Marcelo which was much more rustic than the previous night, but we were given a bottle of wine to keep us warm and a there was a fire which burnt llareta (photo later).

View from the front of Hostal San Marcelo

We woke early to see the geysers nearby, but it was dark when we arrived, and hardly any of my photos turned out. They were much more interesting when I saw them 7 years ago, mostly because we could, um... see them. It was utterly, bitterly cold and windy too. I had ice on my jacket when I got back into the car. We didn’t wait for the sun to come up, and headed on to Salar de Chalviri at 4800m where we watched the sunrise and had breakfast. Some lunatics swam in the thermal baths there.

Salar de Chaviri at sunrise

Salar de Chalviri at Sunrise, with Andean Gull

Emmo and I at Salar de Chalviri at sunrise

Then we drove for about an hour via Laguna Blanca to the beautiful Laguna Verde which is backed by Volcan Licancabur. I had already seen Licanabur from the other side with Brennen while we were in San Pedro de Atacama in Chile. It marks the border between Bolivia and Chile.

Laguna Verde and Volcan Licancabur

Panoramic of Laguna Verde

We returned through Salar de Chalviri and had lunch in Villa Mar a pretty little town in a small, cliffy valley of volcanic rocks.

Villa Mar

Then we visited the Valle de Roca before passing through the Pueblo de Alota, Mina de San Cristobal, and the Pueblo de San Cristobal and arrived back in Uyuni by about 5.30.

The mossy looking llareta which is burnt to keep people warm.

Valle de Roca

Valle de Roca

We caught the train to Villazon later that night, but it broke down near Tupiza, and as a result we had to get a bus from there to Villazon, have an excruciating wait at the border crossing, change buses, get one to Jujuy, and then one to Salta. We arrived in Salta around 7pm, after nearly 21 hours on different forms of transport. We found a comfortable and private place to stay and went to bed early.

We didn't do much the following day... Again, it was a Sunday, and almost everything was shut. But we did go to the Museo de Arqueología de Alta Montaña (MAAM), which is the home to three incredibly well preserved pre-Colombian mummies. Although only one is on display at any one time. The one we saw was really quite amazing. She was totally intact, with original clothing. There's a picture here, or put 'La Doncella' into google images.

We took a plane to BA the following morning.

Once we had passed Peruvian formalities, we crossed a bridge and waited in the line for the Bolivian side of things. Brennen discovered that he had to pay a visa fee of US$135, which needless to say, he was not happy about. After clearing Bolivian customs, we waited for the bus to make its way through the throngs of people and eventually rejoined it. But it was missing some passengers, so we had to wait another hour or so until everyone was on board.

It was three more hours to La Paz and we arrived at about 1.30pm, two and a half hours behind schedule. From the bus station, we walked down the hill to Plaza San Francisco and found a hostel, which was more like a hotel. It had hot showers, and private bathrooms. Luxury. Brennen hadn’t had a hot shower since he left Salta, about two weeks earlier. My last proper hot shower was in San Pedro de Atacama.

But before showering, I went to email Emily with our location. There was an email from her waiting for me that said she was very sick. Unu was correct again - she was going to need a hug. Brennen and I relaxed in luxury in the hotel for the afternoon, and I went to collect Emmo from the airport at 8pm. When she came out of the gates, she looked utterly terrible – totally grey. She’d been vomiting all the night before, and was still feeling terrible. And now she had flown directly to La Paz from sea level, adding altitude sickness to the mix.

We jumped in a cab and headed straight to the hotel where she remained for the night, while Brennen and I went out to get some street meat for dinner and then a beer at a Cuban bar.

The next morning after sleeping in a little bit, Emmo was feeling better, so we headed out to the Mercado Negro (Black Market). We walked around a bit, and saw some hilarious mannequins around the place. Brennen and I were giggling like school girls at them. Em found them less amusing. I’ll put pictures up of them up in another post.

We kept walking around and then a man tried to pickpocket me. I caught him in the act, and called him a thief, looking around to see if anyone cared. No one did. I grabbed his arm and said it again, to which he responded ‘Que pasa!!’, and pushed me away. It wasn’t really worth pursuing, because I’d caught him before he got anything, so he just walked away. But I spent the rest of the morning with my hands in my pockets and my camera stowed safely away, feeling very uncomfortable.

After the market, we headed to a lookout in a park called Laikakota, on top of a small hill near the centre of town. It was full of play equipment and families having fun, and the view was quite nice too.

Em and the Bren-dog at Laikakota.

Panoramic view of La Paz from the lookout

We headed back to the hotel to rest for a while and Brennen randomly bumped into Yasmin when he was getting money from the ATM. She was meeting up with Alex and Luci at a nearby restaurant, two girls from Uni who are doing their exchange in Santiago, Chile. We were invited to come along, and joined them at an Indian/Thai/Japanese/Korean (let’s just call it Asian) restaurant which had utterly, utterly terrible service, but quite good food. It would have been nice to know what the dish I ordered had tasted like, but the one they brought me was fine...

The next morning we headed to the Cementario district to find a bus to Copacabana on Lake Titicaca. The bus was relatively easy to find, despite a taxi driver who was going to Desaguadero being particularly unhelpful;

- 'Where's the bus to Copacabana?'

- 'I'm going to Desaguadero, wanna come?'

- 'No, we want the bus to Copacabana.'

- 'What about Desaguadero?'

We boarded the bus for 15 Bolivianos and in around three hours we were in Copa – Copacabana. The price didn’t include a ferry crossing where we had to get off and take a smaller boat for 1.5 Bolivianos while the bus went across (looking slightly unsafe).

Once in Copacabana, we were accosted by people trying to sell us their hostels, and decided to head towards Hostal Sonia, on the corner of Tejada and Murillo. It was a nice place, with a roof-top terrace and a big room with private bathroom and a view of the lake. We checked in and headed down to the beach to have a trouty snack, and a beer while we played cards and watched the sun approach the horizon.

View from the roof of Hostal Sonia

Brennen and I decided to head up the hill to the north of the town, Cerro Calvario, but Em was still feeling the altitude, and decided to remain behind. We walked most of the way up quickly, watched the sunset and headed down when it was getting dark.

Sunset over Lake Titicaca from Cerro Calvario

Copacabana from Cerro Calvario at sunset

Moonrise over Copacabana

We headed home to play cards and book a ticket to the Isla del Sol for the following morning at 8.20.

The boat didn’t really leave Copacabana until about 9.20 and we arrived at the northern port of Isla del Sol (Cha’llapampa) at about 11.30. We were met by a man called Jorge who told us he’d be taking us on a tour of the island. But he wasn’t very good, and managed to lose half of us in the first five minutes. We saw a small museum near the port, and then continued on to the ruins of the temple of the virgins of the sun, and then to Chincana. Then, once the tour was over, he told us that he doesn't earn a salary, and the cost of the tour would be 20 Bolivianos per person. We gave him 10 each. My god we’re cheap. That’s about 1.5 US dollars.

The packed boat on the way to the Isla del Sol

We were planning to walk the 15 or so kilometres back to the Fuente del Inca, where we could catch a return ferry, but with the ferry arriving late to the Isla del Sol, and the tour taking much longer than we expected, it was going to be a crazy rush. The walk was very difficult due to the sun and the altitude, and we really had to push it to make it back to the ferry in time. We almost felt like the tour had been slow on purpose to make us miss the boat and buy another return ticket.

View of Lake Titicaca from the path to Fuente del Inca.

We made it back to the port as the ferry was pulling away, but it was very full, and the driver asked us if we wanted to get the later one. There was a later one? We didn’t know that, and had ended up pushing ourselves to make it to the jetty for no reason. The later one was scheduled to leave at 4pm (in half an hour), but didn’t end up actually going for another hour. We were back in Copacabana by about 5.45, got some dinner and had an early night.

On the ferry back to Copacabana

The next morning we got up early and headed into town to get a bus back to La Paz. It was easy to find a lift, and we were out of Copacabana by about 9am. The ride back to La Paz was uneventful, and once we were back, we headed to the bus station to buy tickets to our relative destinations. Brennen found a 40 hour bus leaving for Buenos Aires immediately (or so he thought) and Em and I booked a bus to Uyuni leaving that night at 8pm. When I was back in BA I found out that Brennen’s trip had actually taken 4 days. If he can be bothered writing about it, I’ll post his nightmare here.

Em and I left our bags with the bus company and had a little wander around La Paz before deciding to go and see a movie. We saw the Karate Kid, which was almost a word for word remake of the original. And quite enjoyable. My favourite scene – Jackie Chan beating up a bunch of 12 year olds.

Then it was back to the bus station and on to Uyuni, after being warned by a traditionally dressed man that we’d need a blanket for the trip. For some reason, we ignored him and threw our bags into the luggage compartment of the bus...

The bus left on time, and we initially got some sleep, but woke at about 1am, frozen to the bone, when the bus made a stop. I jumped off and luckily, some other people were rearranging their things in the baggage-compartment. I saw my bag, grabbed it, and removed the sleeping bag.

From then on things were slightly more comfortable. Em and I huddled under the blanket and got a little more sleep before waking when the sun was rising. The windows of the bus were frozen, as was my water bottle. It’s a little hard to see in the photo, but trust me - it was frozen.

Our bus window as the sun was coming up.

My frozen water bottle

Arriving in Uyuni, we were immediately accosted by people trying to sell us their tour of the region. We were pleased to hear that there were tours leaving that morning at around 11, meaning that we wouldn't have to stay in the town of Uyuni for the night. Everyone seemed to offer the same price – 600 B for three days - so we went with one of them to their office and got organized - had some breakfast, bought some warm things like scarves and gloves, and left for the tour with a French couple who didn't speak much English, and a Belgian couple who did.

OK, the commentary for this section is going to be more boring than normal. We went to a lot of places, OK? So just look at the photos if you get sick of it.

The first stop was the train cemetery about three kms from the centre of town. It was at this stage we realized just how many other people there were doing the same tour. There were about 20 other jeeps and people climbing all over the train engines.

These train tracks were actually still in use.

Next stop was Colchani with its ‘museums’, which could be more accurately described as ‘shops which sell tourist crap’. I took this photo of a car that could've used a lick of paint.

Next stop was the Salar (salt flat) itself, and some of the areas that are being mined for salt. It’s the biggest salt flat in the world with an area of 12,000 km2. Then we visited a hotel made of the stuff.

The salar with little mountains of salt ready to be collected and refined

Next was Isla Incahuasi, aka Isla de los Pescadores with its huge cacti (some of which are over 1000 years old) and it’s geographically isolated community of Viscachas. We climbed to its lookout and had lunch there, and then Em and I walked around the island.

That’s me next to a huge cactus on Isla Incahuasi

I suppose you’ve gotta do one of these when you’re there. It’s worked surprisingly well considering it was a self-timer shot.

Next stop was a place that they collect salt blocks to make buildings, or to carve into touristy trinkets such as salt llamas or ashtrays.

The salt block collection place

An interesting salt crystal which I picked up out of an evaporation pool

Salt encrusted hands.

Then we headed to our lodgings for the night – a hotel made entirely of salt. I wouldn’t have liked to work there because there was a constant mist of salt dust in the air and I felt thirsty the entire time we were there. Not to mention it was frickin’ freezing.

The salt hotel

Sunset from the salt hotel

My God, dinner was ordinary that night. I think they call it Pique a lo Macho, a tradition Bolivian dish. It consists of French fries with chopped hotdog meat, boiled eggs, fried onions and tomatoes heaped into a brown mushy pile. No one could finish a whole plate.

We were up early the next morning, woken by the guide. It was absolutely freezing before sunrise. The guide told us it got to minus 20 outside during the night. We left the hotel around 7.20 and visited the town of San Juan at about 8.15.

Then we passed thru Salar de Chiguana, the military post at Chiguana, and stopped to get a photo of the Ollague Volcano.

Volcan Ollague.

Then – Lagunas Canapa and Hedionda (where we lunched) and some beautiful Jame’s Flamingoes.

Flamingoes at Laguna Canapa

Flamingos in flight at Laguna Hedionda

Flamingos in flight again at Laguna Hedionda

Then we passed Laguna Chiar Kota, Laguna Honda and Laguna Ramaditas, then through an unusual rocky valley filled with more viscachas, and then continued to La Montana de Siete Colores, el Desierto Siloli and stopped at the Arbol de Piedra.

Em with the Arbol de Piedra (Tree Rock)

Then on to Laguna Colorada, which is coloured red due to the algae that live in its waters.

Laguna Colorada

We stayed the night in a hotel called San Marcelo which was much more rustic than the previous night, but we were given a bottle of wine to keep us warm and a there was a fire which burnt llareta (photo later).

View from the front of Hostal San Marcelo

We woke early to see the geysers nearby, but it was dark when we arrived, and hardly any of my photos turned out. They were much more interesting when I saw them 7 years ago, mostly because we could, um... see them. It was utterly, bitterly cold and windy too. I had ice on my jacket when I got back into the car. We didn’t wait for the sun to come up, and headed on to Salar de Chalviri at 4800m where we watched the sunrise and had breakfast. Some lunatics swam in the thermal baths there.

Salar de Chaviri at sunrise

Salar de Chalviri at Sunrise, with Andean Gull

Emmo and I at Salar de Chalviri at sunrise

Then we drove for about an hour via Laguna Blanca to the beautiful Laguna Verde which is backed by Volcan Licancabur. I had already seen Licanabur from the other side with Brennen while we were in San Pedro de Atacama in Chile. It marks the border between Bolivia and Chile.

Laguna Verde and Volcan Licancabur

Panoramic of Laguna Verde

We returned through Salar de Chalviri and had lunch in Villa Mar a pretty little town in a small, cliffy valley of volcanic rocks.

Villa Mar

Then we visited the Valle de Roca before passing through the Pueblo de Alota, Mina de San Cristobal, and the Pueblo de San Cristobal and arrived back in Uyuni by about 5.30.

The mossy looking llareta which is burnt to keep people warm.

Valle de Roca

Valle de Roca

We caught the train to Villazon later that night, but it broke down near Tupiza, and as a result we had to get a bus from there to Villazon, have an excruciating wait at the border crossing, change buses, get one to Jujuy, and then one to Salta. We arrived in Salta around 7pm, after nearly 21 hours on different forms of transport. We found a comfortable and private place to stay and went to bed early.

We didn't do much the following day... Again, it was a Sunday, and almost everything was shut. But we did go to the Museo de Arqueología de Alta Montaña (MAAM), which is the home to three incredibly well preserved pre-Colombian mummies. Although only one is on display at any one time. The one we saw was really quite amazing. She was totally intact, with original clothing. There's a picture here, or put 'La Doncella' into google images.

We took a plane to BA the following morning.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)